9 Vintage Grocery Stores That No Longer Exist (But Older Generations Will Remember)

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Some people are as devoted to their grocery store as they are their favorite sports team. Whether it's a mammoth nationwide chain or a beloved neighborhood outlet, they can't imagine shopping anywhere else. In 21st-century America, we buy our groceries (and a lot more besides) from a variety of places, some of which have been successfully trading for, well, as long as we care to remember.

But step back in time just a few decades, and names that were once giants of the retail grocery landscape come into view. Before Costco, Walmart, or Sam's Club dominated the market, others ruled supreme, earning our grandparents' and parents' loyalty through quality products and great customer service. These stores attracted thousands of dedicated shoppers for years, only to fall victim to shifting tastes and trends or economic hard times — though that's an issue unlikely to affect this chain.

Today, they are little more than faded pictures on social media feeds; the subject of nostalgic conversations that always begin with the question, "Do you remember when?" Let's lift the lid on these blasts from the past, with our pick of vintage grocery stores that are no longer around, but older generations will fondly remember.

A&P

So much of what we find commonplace in supermarkets today, from wheeled carts to "own brand" products, can be traced back to the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company. Founded in 1859, it was rebranded a decade later with just 11 stores to its name. By 1930, it had more than 15,730 across the United States and Canada. What was the secret to A&P's phenomenal success? A revolutionary approach.

Alongside its own-brand coffee, A&P stores only stocked items that sold well — potentially pioneering the notion of discontinued grocery products. It had introduced a customer reward program in the 19th century and, by 1912, launched the first of its "economy" stores, with lower prices that undercut independent outlets. In subsequent years, A&P sold fresh meat, fruit and vegetables, and bread in several stores, everyday items in modern supermarkets, not so much in the 1920s and '30s.

It snapped up supply chain businesses, from dairies to canning production. Self-service and shopping carts made the experience more convenient for customers, and A&P's currency soared in the post-war years. However, by the end of the 1960s, several outlets were failing, and the store pivoted to a warehouse economy outlet model. A succession of CEOs and acquisitions failed to shore up the quickly declining A&P, while rivals like Walmart, which responded more nimbly to changing customer demand, overtook the chain as it struggled financially. In 2015, the last remaining A&P outlets were shuttered.

Alpha Beta

There are a lot of fond memories online from people who grew up with, or worked at their local Alpha Beta grocery store. Stories of day-old bread being given away, buying a cupcake at the end of a well-timed family shopping trip, or retiring after decades of service as an employee, paint a picture of a place that was more than just somewhere to buy stuff. Yet the history of the Alpha Beta brand belies the rose-tinted views on social media.

Founded by brothers Hugh and Albert Gerrard, who based it on the alphabetical arrangement of goods in their Triangle Grocerteria in 1915, the first Alpha Beta outlet launched in Pomona, two years later. In 1918, it had grown to seven stores, but it took until 1932 for the first supermarkets to launch. By 1945, customers could happily shop at 20 Alpha Beta-branded outlets and, over the next 40 years, that figure rose to more than 200 stores, spread across several states, including California, Texas, New Mexico, and Oklahoma.

In 1961, Alpha Beta merged with American Stores, but in 1988, the latter's decision to absorb Lucky Stores was a fateful one. Although the $2.5 billion merger created the biggest supermarket company in the United States, Alpha Beta was only a small part of it. That vulnerability was clear when American Stores ditched the 73-year-old name in favor of Lucky, the first of several rebrands as Alpha Beta stores faded from communities after being sold to different buyers.

Dominick's

People shopping at their local supermarket expect quality products and affordable prices, all wrapped up with great customer service. While most customers would grudgingly admit that getting two out of three ain't bad, regulars at Dominick's were guaranteed all three. It was one of the reasons the Chicago-centered chain was so successful – and a key component in the architecture of its demise.

Italian immigrant Dominick DiMatteo began trading in Chicago's West Side in 1918, but business really took off in 1950 with Dominick's Finer Foods, a 14,000-square-foot supermarket. The family-owned business flourished, despite a sale to and subsequent buy back from Fisher Foods Inc. As the decades rolled by, Dominick's conquered the suburbs, partnering with Starbucks to deploy coffee bars at stores, and using nascent digital technology to make shopping easier for customers.

In 1993, after the death of Dominick di Matteo, the business was sold and new owner Yucapia rolled out the "Fresh Store" concept. A successful few years ensued, and Dominick's was put up for sale again, this time acquired in 1998 by Safeway. The downward spiral soon followed. Much-loved local products were replaced with unfamiliar Safeway standards, while the long-standing tradition of filling customers' personalized orders stopped. By the early 2000s, union unrest prompted Safeway to seek a new buyer for Dominick's, but instead shuttered the brand before the decade was out.

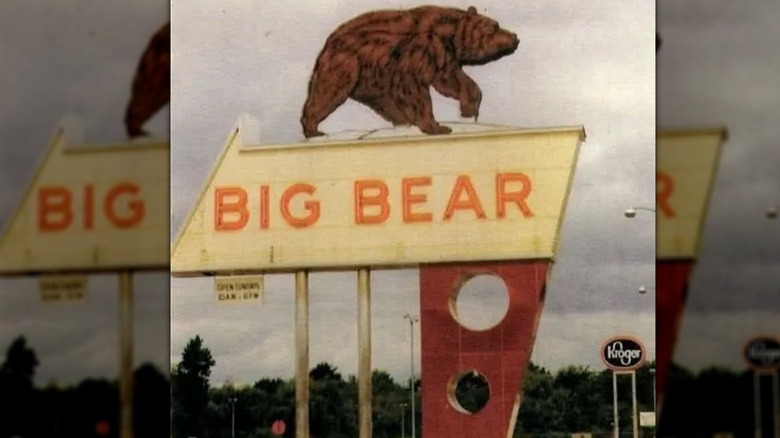

Big Bear

In 2025, a French supermarket advert featuring a lonely wolf won hearts around the world. But it wasn't the first time a forest animal encouraged customers to visit a store. People who shopped at the inaugural Big Bear supermarket in Columbus were used to seeing a live bear, kept in a cage outside the store. It was just one of founder Wayne E. Brown's ways to bring in the crowds, though luckily they didn't all include semi-wild animals.

Technology helped drive Big Bear stores forward. Brown's stores broke new ground with the use of motorized conveyor belts that were operated by cashiers, and created service departments covering everything from meat and deli to baked and fresh produce, all with a focus on quality. Brown's stores bought in bulk and relied on that volume to make up for his wafer-thin margins to turn a profit. Rival store owners seethed and put pressure on suppliers to sidestep Big Bear, forcing it to find alternatives.

Ironically, the model that made it a roaring success became a template for new competitors, chains that could sell even more cheaply than Big Bear. In 1989, the ailing brand was bought out by the Penn Traffic Company, which itself folded in 2004. Some Big Bear stores were repurposed by other businesses, and former employees left to mourn its glory days on social media. As for the bear? He retired to a zoo.

National Tea Co.

Danish immigrant George Rasmussen opened his first Chicago grocery store in 1899 and by the time he died in 1936, his National Tea Co. (operating as National Foods) had survived the Great Depression, and grown to more than 1,220 stores in eight states. But beneath the seemingly positive numbers, Rasmussen's business was in bad shape. When Chicago printing magnate John F. Cuneo bought it in 1945, he dubbed it "the worst chain-store property in the country," per Time. Luckily, his choice of president, Harley V. McNamara, proved inspired.

He turned around National Tea's fortunes and made it the fifth biggest supermarket chain in the United States. McNamara put buying power into the hands of local managers, who could better cater to their customers' needs — and pocketbooks — bought out rivals, and set up stores in new locations across Chicago and beyond. People clearly loved National Foods, reminiscing on social media about their long working careers and sipping own-label flavored sodas, and throughout the 1950s, National expanded by snapping up other brands, before it was bought by Canada's Loblaw.

The purchase seemed to be successful – until the 1970s, when Loblaw began selling off poorly performing National outlets. In 1995, the Canadian company sold the chain to Schnuck Markets for around $215 million, which handed off 29 New Orleans stores to Schwegmann Giant Super Markets, the following year. By the time the acquisitional dust had settled, the National Tea Co. and National Foods brands were a memory.

Schwegmann Giant Super Markets

There aren't many heroes in the retail grocery space, but John G. Schwegmann was just that to millions of Louisiana shoppers. He opened Schwegmann Bros. Giant Supermarket in 1946, the first in a chain of vast stores that broke the mold in many different ways. John G. Schwegmann's hard-won battle against price-fixing, which went all the way to the Supreme Court, protected shoppers, while his supermarkets offered them a wide range of products apart from groceries, including gas, and services like banking and shoe repairs.

Schwegmann's prioritized its customers' needs over making an easy buck, and was rewarded with unstinting loyalty for decades. Skylar Dillon described how her grandparents, who were struggling to make ends meet, brought home 23 grocery bags after their first trip to Schwegmann's. "It created an opportunity to provide for their kids in ways they would not have been able to otherwise," she wrote, per Via Nola Vie.

In "The People's Grocer John G. Schwegmann," biographer David Cappello described the retailer as "a fierce consumer crusader," and while that drive helped make his supermarket chain great, when Schwegmann died in 1995, there was nothing to replace it. Two years later, the chain was bought by Kohlberg and the Schwegmann family's control of the business was brought to an end as the founder's grandson stepped down. By 1999, all Schwegmann Giant Super Markets had closed.

Dahl's

In 1980, the first-ever Whole Foods Market opened its doors, but its focus on locally grown, fresh produce wasn't as new as the founders might have thought. Shoppers in the Midwest had enjoyed that experience for just over 50 years, thanks to the Dahl's chain of supermarkets. Founded by Wolverine Thilbert "W.T." Dahl in 1931, he partnered with his brother-in-law, Frank DePuydt, to launch a supermarket in 1948, notable for being the only one between the Rocky Mountains and the Mississippi River to have an in-store bakery.

Two years later, the relationship between DePuydt and Dahl had soured. The latter outbid his former partner to take complete control of the brand, and in 1952, Dahl cut the ribbon on a 21,000-square-foot supermarket – the largest in the Midwest. People were devoted to Dahl's stores. Nostalgic social media threads are outpourings of love, from those who remember their parents shopping at Dahl's. One former employee said they remembered "everyone being pleasant and kind."

Sadly, nothing could protect Dahl's, a relatively small chain, from bigger rivals with more buying power. In 1970, W.T. handed control of the business to an employee group, which launched a stock ownership plan five years later. A 1979 expansion into Missouri proved catastrophic and, despite Dahl's carrying out the first grocery debit card transaction in the United States in 1981, the company was struggling. In November 2014, Dahl's filed for bankruptcy, and a few months later was sold to Associated Wholesale Grocers.

Pathmark

Few grocery stores have such a short, yet tangled history as the Pathmark chain. A subsidiary of Supermarkets General, which split from the Wakefern cooperative in 1968, Pathmark was the new name given to existing Shop-Rite outlets and a major moneymaker in the Northeast for Supermarkets General. They were also popular with customers, not only for the wide range of goods they stocked, including records and clothes, and their use of innovative technology like checkout scanners, but also because they were one of the few to open 24/7.

Pathmark continued to grow in the 1970s and '80s, opening the first of its Super Centers and a 42,600-square-foot store in Manhattan in 1983. However, by the end of the 1980s, the brand was rubbished in a Forbes article, which called some stores dirty and outdated. The criticism did not halt another decade of expansion, while Supermarkets General racked up $20 million in losses.

When a 1999 buyout of Pathmark was nixed by regulators, it filed for bankruptcy the following year. In 2007, It was bought by A&P for $1.3 billion, infuriating members of the Local 1500 union. In 2015, as the final outlet closed, a blog said "an ever changing cast of A&P executives ran these once profitable stores into the ground," via UFCW1500. While the Pathmark brand has been resurrected by other companies, those who loved the original can only reminisce on social media.

White Hen Pantry

Ask anyone who shopped at a White Hen Pantry store back in the day and they'll tell you how good the coffee was, the bliss of biting into one of their freshly made turkey sandwiches, or the hours-long sugar boost you got from the iced brownies. For many shoppers in Chicago and Boston, it was, quite simply, the best convenience store. In 2006 there were more than 250 White Hen Pantry stores, but it began in 1965, after the Jewel Tea Company rebranded its Kwik Shoppe stores.

The White Hen Pantry stores copied 7-Eleven outlets and were set up as franchises, initially deployed in suburban locations, where shoppers filled their carts with treats from the store's in-house bakery and deli sections. For more than a decade, the brand continued to expand throughout Chicago and into Boston, becoming much-loved fixtures in their communities. Then, in 1984, American Stores Company bought Jewel, and chairman Sam Skaggs decided that White Hen Pantry wasn't part of his vision.

After being sold twice, including once to its own managers, the third company to buy White Hen Pantry was, with incredible irony, the one behind its successful business model. In 2006, 7-Eleven paid $35 million for the chain, its biggest purchase for 20 years. Although the company insisted at the time there would be no "immediate" changes, over several years, all White Hen Pantry stores were converted to 7-Elevens.