13 Things To Avoid Ordering From Seafood Restaurants, According To Experts

Food is often at the mercy of fashions, and lobster is a great example. Unaffectionately dubbed the "cockroach of the sea," for decades, its fortunes were turned around with the advent of canning and the railway. Today, it's a gourmet delicacy in many restaurants. However, while some seafood trends are fickle, others are immovable.

Shrimp is a favorite in the United States, yet it's part of a vast range of fish shapes, sizes, and flavors. Experts warn around 90% of Americans don't eat the recommended minimum 8 ounces of seafood a week, despite health benefits including being a good source of omega-3 fatty acids and protein, per the Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior.

Unfortunately, many restaurant-quality fish also come with other, less palatable extras, from chemical contamination to fishing practices that harm marine ecosystems. To ensure we are as informed as possible when eating out, Andre Barbero, head chef at Harpoon Willy's, Sheila Lucero, culinary director at The Big Red F Restaurant Group, and Kyle Foley, sustainable seafood program manager at Gulf of Maine Research Institute offered their thoughts on what we should think twice about when ordering from seafood restaurants.

The pasta special

In 2018, an FDA labeling rule forced restaurants to display information about the nutrition and calories their dishes contained. Although regulations mean they must also inform customers about any allergens, eateries are not obliged to detail every ingredient they use. That leaves a lot of leeway when it comes to menu items such as pasta specials. Although Sheila Lucero would have no problem ordering one from a restaurant she had never visited before, Andre Barbero is more skeptical.

He advises potential diners to be wary of "all-you-can-eat" seafood deals, especially if it's somewhere new to them, because they may rely on lower-quality or unsustainable sources for the fish. "Specials can be fantastic when they're truly seasonal or creative, but sometimes they're used to move product that's been sitting a bit too long," he said. Barbero's experience as a chef meant he could tell whether a special was worth trying by how the menu had been written and the kitchen was run. His advice to those outside the business? Give "mystery fish" or vague dishes such as "whitefish special" that have no specifics a wide berth.

Swordfish, tilefish, shark, and king mackerel

On the face of it, these four species of fish have a lot going for them. Swordfish are great sources of B vitamins, likewise king mackerel, which also contains lots of omega-3 fatty acids. Tilefish is good for phosphorus and niacin, and is low in salt, while shark rates as zero on the glycemic index and is loaded with selenium.

Unfortunately, they also contain the highest levels of mercury, which can cause everything from anxiety to muscle weakness. In severe cases, it can impact our cardiovascular system and internal organs. These fish should be avoided by young children aged up to 11, anyone trying to get or who is pregnant, and those who are breastfeeding, according to the FDA. All three of our experts said consumers should take warnings about mercury levels seriously.

For adults who eat a lot of fish, mercury can pose a health risk over the long term, but for the groups mentioned by the FDA, eating swordfish, tilefish, shark, and king mackerel is more immediately dangerous. Kyle Foley and Sheila Lucero both encouraged diners to switch to fish and shellfish with much lower mercury concentrations, such as salmon, trout, shrimp, oysters, and clams.

Stone crab

Few things match the joy of digging out a juicy morsel of meat from a freshly hammered crab claw: It's activity food at its finest. Dungeness, Blue, King, and Snow crabs are among the most popular kinds, depending on where you are in the United States. Like many types of seafood, crab contains a host of nutrients, including vitamins C and B3. Even better, they're not loaded with mercury, and are among the FDA's list of "Best Choices."

Sadly, for stone crabs, the picture isn't completely perfect. These shellfish are highly prized for their large claws, which are removed before the crab is thrown back into the water, where it takes around 18 months for the limb to grow back – if the animal survives. Florida has very strict laws about stone crab fishing, including a limited fishing period, minimum claw sizes, and not fishing egg-bearing females.

Despite all these rules, stone crabs from the state's Gulf of Mexico coast are rated as red due to overfishing in the region, as well as the risk of bottlenose dolphins becoming bycatch. Researchers are also assessing the negative environmental impact of Bahamian sea-floor traps used to catch stone crabs. The next time you see stone crabs on the menu, if they're from Florida, think twice.

Catfish

Catfish is both a noun and a verb, and Merriam-Webster defines the latter as "to deceive (someone) by creating a false personal profile online." There's a good reason why the name of this popular fish (though don't make this mistake) has been commandeered for dodgier purposes: It is used by unscrupulous restaurateurs as a cheaper alternative to white fish including sole, haddock or cod. Ironically, catfish itself can also be swapped out for swai, shipped in from Asia.

The practice is known as mislabeling. Quite apart from simple economics — consumers could be paying top dollar for an inferior fish — there are health issues, too, especially concerning allergens, as well as concerns around kosher fish. Although catfish can be mislabeled as a different fish and be used as a replacement, the problem kicks into another gear with two other species.

A 2025 study found that amberjack was mislabeled in more than 87% of samples, and red snapper in more than 85%, with the latter often switched out for tilapia. The solution, according to our experts? Ask questions. Sheila Lucero recommended talking to the server while reading a menu, while Andre Barbeo said, "If a restaurant can tell you where their fish came from and when it was caught, that's a good sign."

Shark fin soup

Caviar, olive wagyu, and truffles are popular food luxuries in the United States and Europe but for centuries in China, the most exclusive dish was shark fin soup. It's still the centerpiece of events in Southeast Asia, like weddings and New Year celebrations, and the booming Chinese economy means more people can afford this delicacy.

Ironically, the shark's fins in the soup have very little flavor in and of themselves. They have a texture like noodles or tofu, and absorb the taste of the broth they're served in. The dish is also used as part of traditional Chinese medicine, even though it is laden with harmful chemicals such as mercury. But that's not the only major problem with shark fin soup.

As the name suggests, it is made from the creature's fins — and nothing else. Fishermen target species that are over 5 feet long to ensure the quality of the cut fins, throwing the still-living shark back into the water. The practice kills up to 100 million sharks every year, despite the species facing the risk of extinction.

Farmed salmon

For anyone looking for a source of animal proteins, fish like salmon, can be a climate-smart choice. "It's incredibly good for our health to eat a diversity of seafood," Kyle Foley said, adding it was also good for coastal communities and harvesters to have a variety of ways to make a living. "When seafood is responsibly harvested, it is a win-win-win." That does not apply to farmed salmon.

In the United States, land-based aquaculture — raising salmon in contained, highly controlled environments — is on the up. However, it has a long way to go before it can compete with commercial, ocean-based salmon farms which, although they have boosted supplies of America's second most-popular fish, have wreaked havoc on the marine environment.

Four pounds of wild fish are needed to raise a single pound of farmed salmon, putting massive pressure on the former stocks. The waste produced by salmon farms not only alters the sea bed, it also enables disease to run rampant in wild species, despite the use of antibiotics that can increase resistance in humans. Possibly most disturbing of all, the offspring of farmed and wild salmon lack some of the basic instincts they need to survive.

Atlantic halibut and cod

Many restaurants in the United States have the mild, buttery flatfish halibut on their menus and, thanks to those flaky fillets, cod (whose close family member is a fast food fave) is among the country's most popular fish. Unfortunately, both are victims of their own success and at risk of overfishing. Halibut numbers are as "well below target levels," via the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), though a rebuilding plan is in place that allows limited fishing to continue while halibut stocks recover.

The picture is a little more complex for Atlantic cod. Seafood Watch recommends people only eat fish caught in the U.S. Gulf of Maine or U.S. Georges Bank. These Atlantic cod are yellow rated, which means they are caught under "moderately effective or better" fishery management. Customers are advised to avoid all other Atlantic cod, not just because of their low numbers, but also the negative impact of bycatch.

For Andre Barbero, removing vulnerable fish species from menus is the responsible thing to do, but insists diners should be more informed. "Awareness leads to demand for better practices across the industry," he said. For Kyle Foley, it's a more nuanced picture. "Avoiding eating the cod they do bring to shore just hurts fishermen who are following very strict rules to try to protect the rest of the cod population."

White tuna/escolar

The Hawaiian name for escolar is maku'u, which translates as "exploding intestines," and it's also known as the "Ex-Lax fish." They're fairly unambiguous clues about the impact escolar — sometimes known as white tuna — has on diners. It has been banned in Japan since 1981, but has been available to buy and eat in the U.S. since a temporary ban was lifted in 1992. So, what's the problem with white tuna?

First of all, it's not tuna: Only albacore can be designated "white," so seeing it on a restaurant menu should immediately raise a red flag. Second, it's also high in mercury, and third, it's associated with environmentally harmful fishing practices. However, there's one issue associated with escolar that should make diners not just think twice about ordering it, but avoid it altogether.

Escolar is packed to the gills with fats known as wax esters which are very difficult for humans to digest. Eating more than 3 ounces of escolar can lead to keriorrhea, symptoms of which include "diarrhea, abdominal cramps, nausea, headache, and vomiting," via Science Direct. It's not food poisoning but the body expelling the indigestible oil.

Orange roughy

Restaurant chefs and diners across the United States are big fans of orange roughy – previously known as the rather less appetizing "slimehead" — because of its pure white, boneless fillets and their mild flavor. It's also known as deep sea perch.

Orange roughy is also on the FDA's list of fish to avoid, as it's high in mercury, but that doesn't seem to have dented its popularity in the U.S. Sheila Lucero prefers not to tell people what they should or should not eat, but explained, "I do encourage avoiding species that are overfished or harvested unsustainably." She aims to offer tasty alternatives that are more environmentally conscious.

"For me, it's about guiding guests toward choices that support healthy fisheries rather than putting any one dish on a 'do not order' list," Lucero said. Andre Barbero suggested diners could be more selective about where they choose to eat, "In fine dining or chef-driven spots, you'll often see a commitment to sustainable sourcing. In volume-driven operations, that awareness isn't always there."

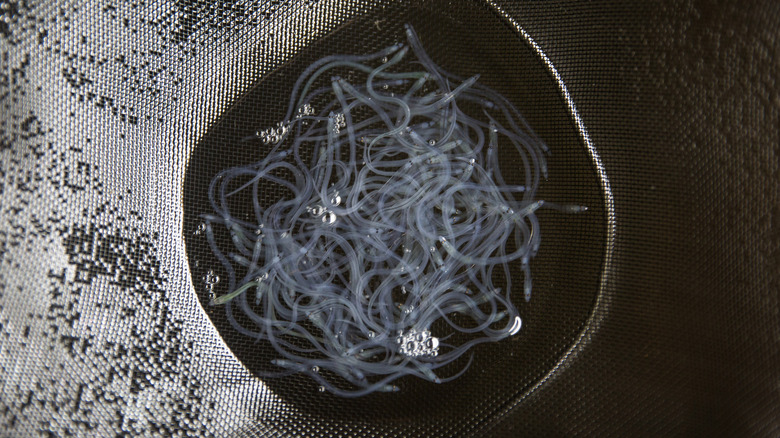

Eel

The chances of diners spotting eel dishes on the average restaurant menu are pretty low, but for sushi lovers, it's a very different story. Much of what is sold in the United States contains unagi — the Japanese word for eel — but demand for sushi, in the U.S. and worldwide, has pushed some of these fish stocks to critically endangered status.

Many of the eels used in American sushi are raised as baby glass eels in Maine, sent overseas (mostly to farms in China) to fatten up before being sold back. The U.S. imports around 11 million pounds of eels annually, most of which goes to the sushi industry, at a cost of over $2,000 per pound. It has given rise to a black market described as the "biggest wildlife crime by value on Earth," via ChatEurope.

Millions of baby glass eels are illegally trafficked each year, a problem that isn't helped by the legitimate but long-winded growing and exporting process. Historically low stock numbers through overfishing and poaching isn't the only challenge facing the eel. Pollution and the effects of climate change are also destroying habitats. While companies like American Unagi are banging the drum for sustainable, home-grown eels, sushi lovers should think twice before placing their next order.

Octopus

Octopuses are incredible creatures: They can live in cold or warm waters, they have three hearts, all of them are venomous, and their legs effectively make up 60% of their brain. Long a staple of Asian and Mediterranean cooking, octopus is becoming increasingly popular in the United States, thanks to its mild, slightly sweet taste. As well as fears of a decline in some species, there are growing concerns about the methods of catching a species as obviously intelligent as octopuses.

Their decentralized brain means there's no single, painless or quick way to stun bigger species, so they are exposed to extreme cold until they become unconscious. In contrast, smaller octopuses are beaten and turned inside out. Researchers have also called into question the sustainability of recently established octopus farms, warning the creatures are "unsuited" to mass production, while feeding these omnivorous animals can't be done sustainably.

Avoiding octopus on a restaurant menu may be relatively simple, it's trickier for squid, which faces challenges of its own. In 2022, 85,000 tons of squid was either caught or imported into the U.S., per The New York Times, but China rules the roost when it comes to catching and processing it into calamari. However, research has highlighted human rights violations and environmental lawbreaking by both Chinese fishing fleets and processing plants.

Bluefin and bigeye tuna

Canned tuna regularly makes it to the top 10 most popular fish in the United States. Although yellowfin and skipjack tuna are inside the tin, bigeye, among the world's most-fished species, can also be included, so it's always worth reading the label. Tuna is also a popular sushi ingredient, and chef Andre Barbero described the bluefin variety as "a magnificent species under enormous pressure," adding that if it was on a menu, he would skip it.

There are good reasons to think twice when it comes to ordering tuna from a restaurant, especially if it's labelled bluefin or bigeye. Both fish look similar and while some countries have bycatch allowance for bluefin, they do not extend to bigeye. Trouble is, young bigeye tuna often swim with adult skipjack, so they are not only at risk of overfishing, but if caught, can't breed, putting population numbers in danger.

For Pacific bluefin tuna, the situation is already grave. An assessment by the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna concluded that "stock remained below the level estimated to produce maximum sustainable yield." Bluefin and other tuna species all face the same problems: Dwindling populations, illegal and unregulated fishing, and "international conservation management," per WWF. For Sheila Lucero, the choice is clear, "Chefs have a responsibility not to serve species at risk of overfishing."

Location-specific fish in landlocked states

Diners can be forgiven for raising an eyebrow at restaurants with "fresh" fish on the menu but are thousands of miles from the United States' coast, but it might not be the problem we think. Both Kyle Foley and Sheila Lucerno sang the praises of improved freezing technology that allows landlocked eateries to sell seafood that is just as fresh as the places where catches are landed.

"Even for coastal regions, freezing seafood can be a good way to extend the shelf life of local seafood," enthused Foley. As well as giving home cooks and restaurant chefs more flexibility, "it lowers the pressure of having to use that seafood right away," she said. The line becomes a little blurrier for diners when restaurants label a fish as "local" when it's clearly coming from miles away.

Andre Barbero agrees freezing has helped the industry access good quality fish but nonetheless advises customers to pay attention to what's on offer. "If you're 500 miles inland, local seafood probably means freshwater species or farm-raised fish." Whether a restaurant is transparent about it can be an issue. "The important thing is integrity: Don't pretend something is "local" if it isn't."